Worksheet 1: Above and beside

Among other things, GeomLab is a language for describing pictures. The GeomLab program lets you write a description in the left-hand part of the window, and will then show you the corresponding picture in the right-hand part.

To get you started, we have provided several pre-drawn pictures and given them names.

For example, the name man stands for a stick-figure picture of a man:

man |  |

(whenever we show an expression and a picture like this, we mean that GeomLab associates the picture on the right with the description on the left.)

Similarly, woman stands for a stick-figure woman:

woman |  |

There are also pictures named tree and star that you should try out for yourself.

If we have two pictures, then GeomLab lets us put one beside the other using the operator $. So the expression man $ woman stands for the stick-figure man next the the stick-figure woman:

man $ woman |  |

We can also put one copy of the man picture next to another:

man $ man |  |

You shouldn't find it hard to guess what result will come from writing woman $ man, but (if you have this worksheet on paper) you might like to sketch it in the space below before trying it with the GeomLab program:

woman $ man |  |

There's another operator, written &, that puts one picture above another:

woman & man |  |

Just as the order of the pictures matters with $, so it matters with & also, as we can see here:

man & woman |  |

I hope you can see for yourself how to get this next picture:

|  |

So far, we have used the operators $ and & to combine pictures given by their names, but it is also possible to combine pictures in more than one stage, using the result of one operation as an input to another.

For example, we can put a man, a woman and a tree all in a row like this:

(man $ woman) $ tree |  |

I have used brackets in this expression, just the same way that they are used in an algebraic expression like (x + y) + z, to ensure that the man and the woman are combined first, and then the tree is put to their right.

As it happens, in this case it doesn't matter, because putting in the brackets the other way gives the same result:

man $ (woman $ tree) |  |

This is similar to ordinary algebra, where the equation

(x + y) + z = x + (y + z)

is always true. Use GeomLab to check that you really do get the same picture from both the expressions shown above. Then do an experiment with two expressions that put a man, a tree and a star into a vertical column.

Like addition and multiplication in algebra, the operations $ and & are associative, in that the equations

(p $ q) $ r = p $ (q $ r)

and

(p & q) & r = p & (q & r)

are always true. As we saw earlier, though, these operations are not commutative, because man $ woman and woman $ man are different pictures.

Now let's try using both $ and & in the same expression. Try this:

man $ (woman & tree) |  |

Something new is happening here.

When GeomLab combines two pictures

using $, their sizes are adjusted so that the pictures

have the same height, without changing the shape of either

picture. Since woman & tree is naturally twice the height of the single picture man, that picture is shrunk to half size before joining it with the man. (Whatever the size of the resulting picture, GeomLab draws it as large as possible on the computer screen.)

Although this rule seems new, in fact it is consistent with what we have seen already, because the heights of man and woman already match, and when we form man $ woman so do their natural widths.

If you look at the pictures man $ star and man & star, however, you will see that the relative sizes of man and star are different in the two cases, so that the heights match when they are put side-by-side, but it is the widths that are made to match when one is put atop the other.

The next thing to notice is that the brackets do matter in the expression man $ (woman & tree), because (man $ woman) & tree is a different picture:

(man $ woman) & tree |  |

Thinking of algebra again, this fact becomes less surprising. We know that 3 × (4 + 5) is different from (3 × 4) + 5; in fact one of them evaluates to 27 and the other to 17.

In algebra, there are conventions about which of these expressions is meant if we write 3 × 4 + 5 without brackets. The × operation is said to bind more tightly or have a higher priority than the +, and that obliges us to read the expression as if it were (3 × 4) + 5 = 17.

Similarly, there is a rule in GeomLab that $ binds more tightly than &, and that allows us to predict the result when we leave out the brackets:

man $ woman & tree |  |

Try it!

Although this rule allows us to predict what will happen when brackets are left out, we are still free to put them in when we want to force another interpretation, like this:

man $ (man $ tree & woman) |  |

Can you work out what expression gives this picture?

|  |

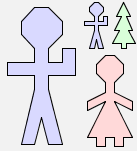

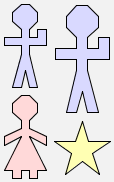

Now look at this picture:

(man $ tree) & (woman $ man) |  |

Both expressions give the same picture (try it!), so these two expressions are equivalent.

If the pictures p, q, r and s all have the same

shape (as they do here), then the two expressions

(p $ q) & (r $ s)

and

(p & r) $ (q & s)

produce the same picture.

But if the component pictures have different shapes, this is not

always true. For example, applying the rule to

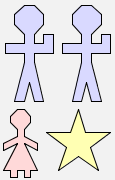

((man $ man) & (woman $ star) we get two different pictures:

(man $ man) & (woman $ star) |  |

(man & woman) $ (man & star) |  |

We can see that the two pictures are not the same, since the sizes of some of the figures have come out differently. If you are good at algebra, you might like to try to work out exactly when the equation

(p $ q) & (r $ s) = (p & r) $ (q & s)

is true for four pictures p, q, r and s.

A hint: it has to do with the ratios between

the widths and the heights of the pictures. The scaling rule of

GeomLab means that these ratios do not change when the pictures are

scaled up or down; both sides of the equation will give the same

result if the boundaries between the pictures meet in a point.

In this sheet, we have seen that it makes to work with formulas whose

values are not numbers but pictures. We can have constants that stand

for fixed pictures, and we can have operators that combine pictures to

make new ones. Just as in ordinary algebra, it makes sense to think

about the relative priority of the operators: just as convention

dictates that multiplication is done before addition where they appear

together in a formula, we can make the convention that $

is done before &.

In ordinary algebra, some equations are true no matter what values

we put for the variables they contain: for example, the equation

a + (b + c) = (a + b) + c expresses the fact that addition

is associative. Similarly, we can look for equations that always hold

between formulas in our new kind of algebra.

Looking beyond this little world of pictures, there are many places in programming and computer science where the algebraic idea of having a set of values with operations on them is relevant. For example, tables of information in databases can be combined with algebraic operations that match the values in a column of one table with values that appear in a different column of another table. This is a good way of organising a database system so that people who use it in their programs are insulated from the way the data is stored.