Fault-tolerance by construction

PPLV Group Seminar, 2026

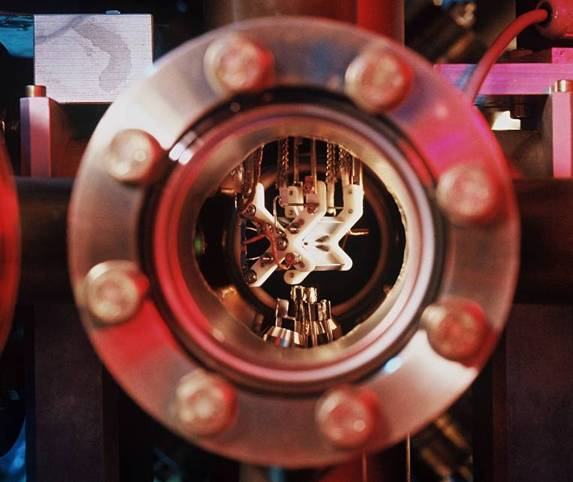

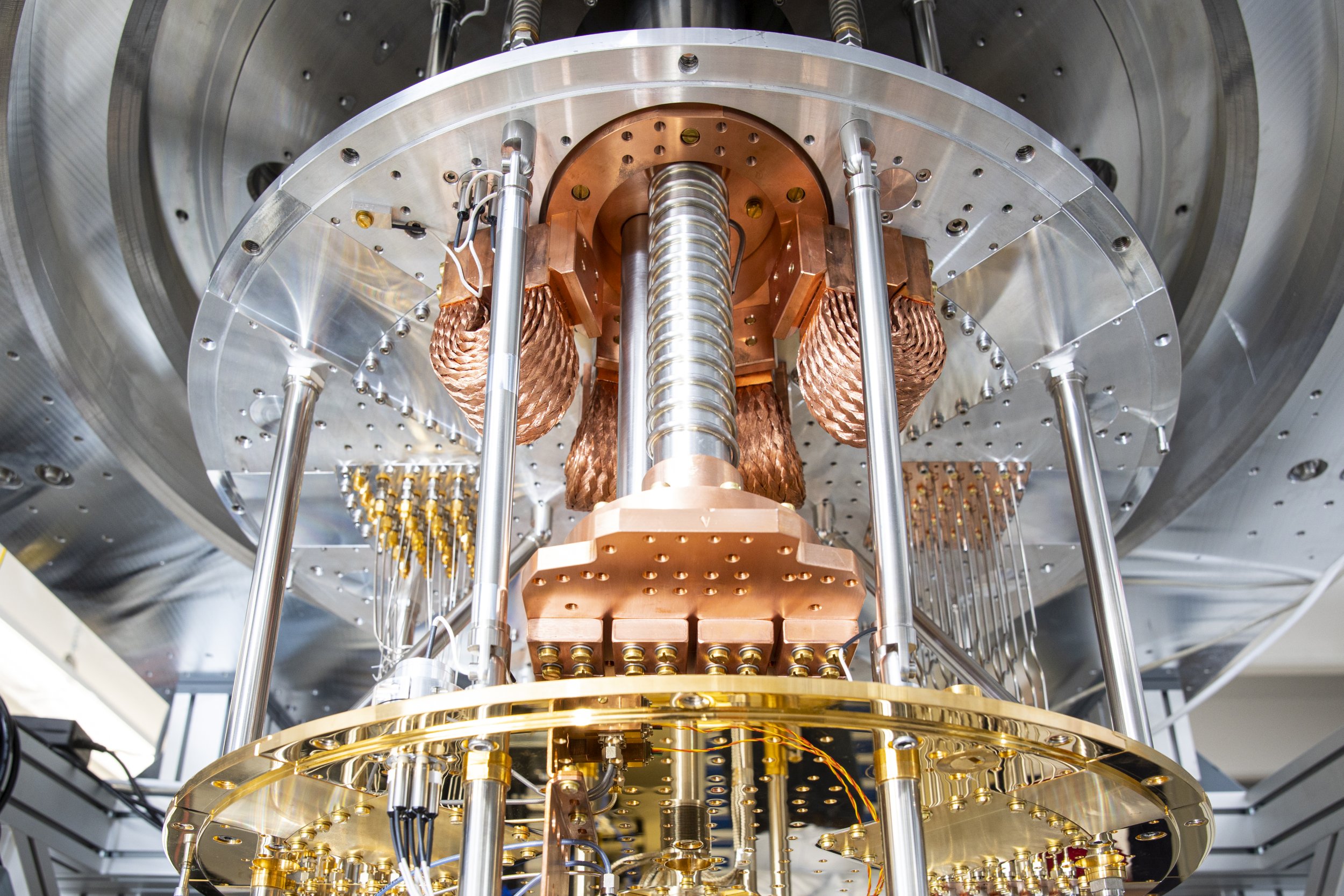

Quantum computing

Quantum computers encode data in quantum systems,

which enables us to do computations in totally new ways.

Quantum Software

the code that runs on a quantum computer

|

INIT 5 CNOT 1 0 H 2 Z 3 H 0 H 1 CNOT 4 2 ... |

↔ |

Quantum Software

code that makes that code (better)

|

|

|

| Optimisation | Simulation & Verification | Error Correction |

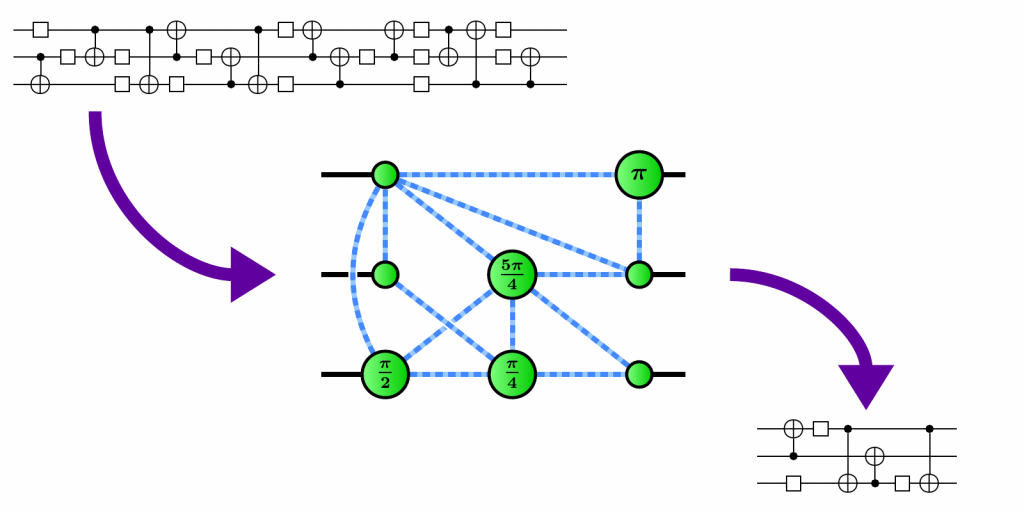

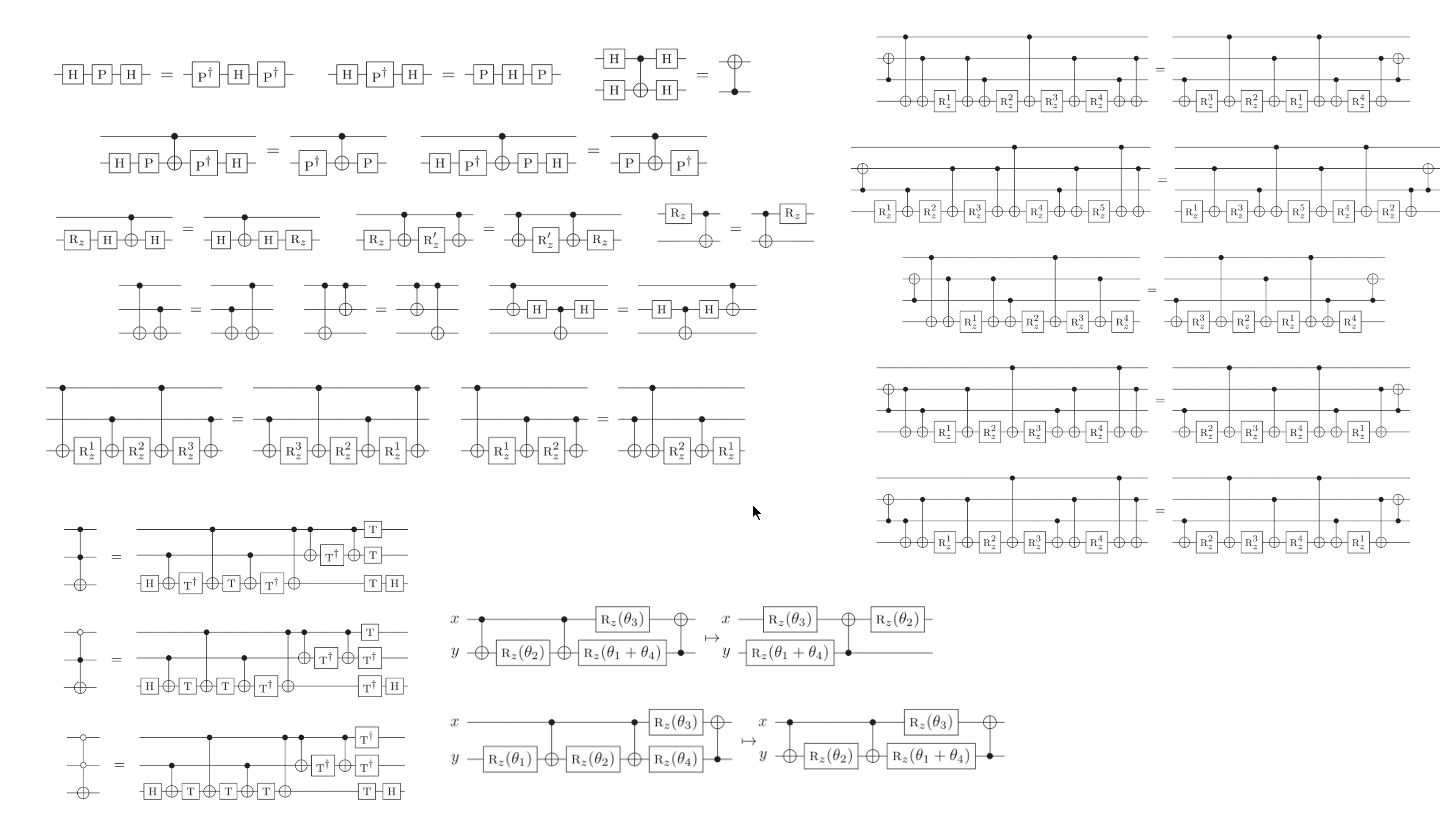

Optimising circuits the old-fashioned way

...

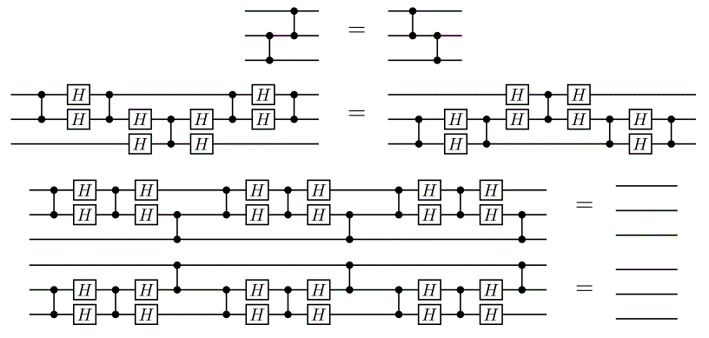

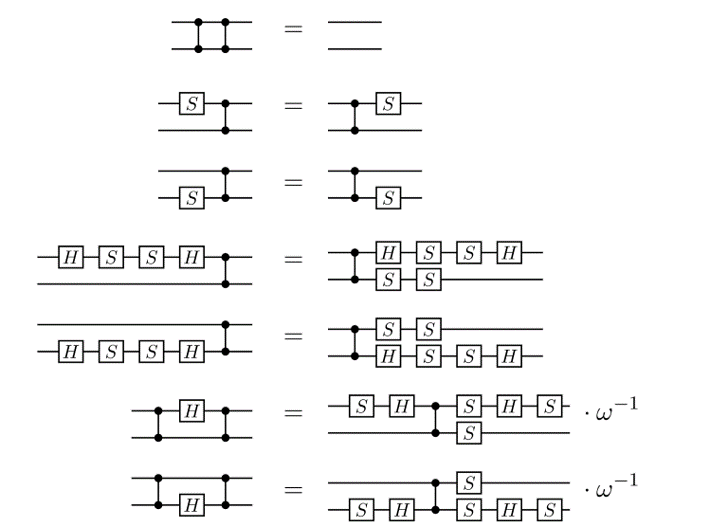

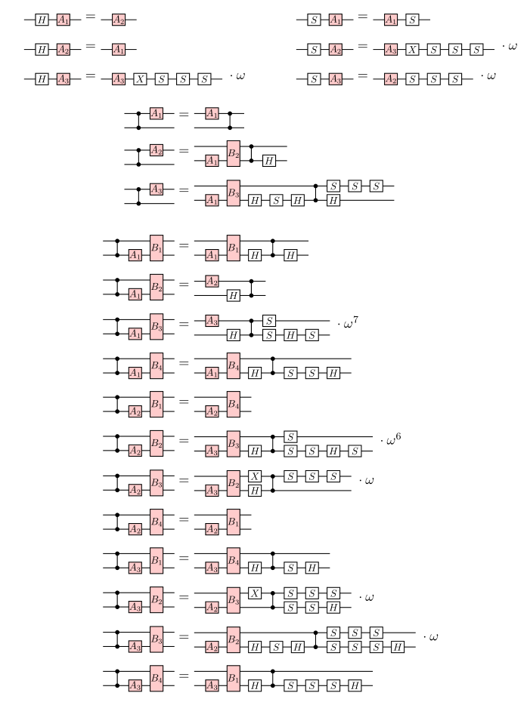

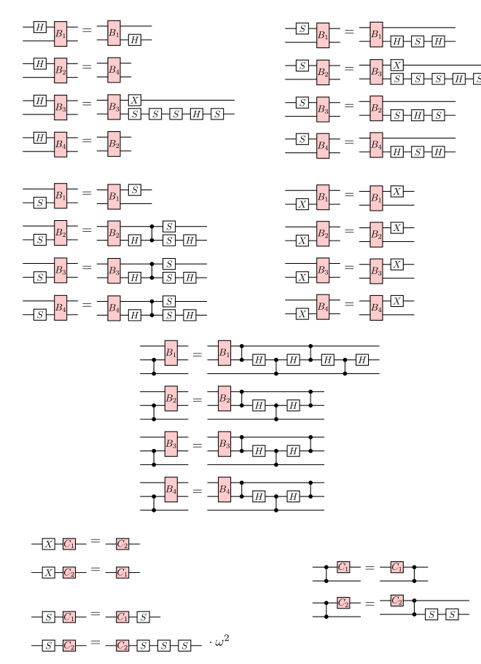

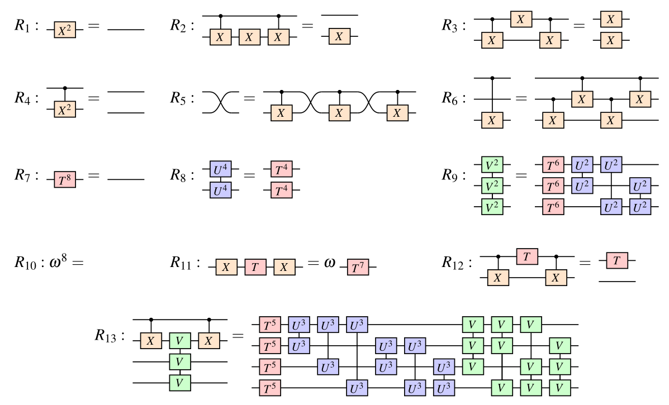

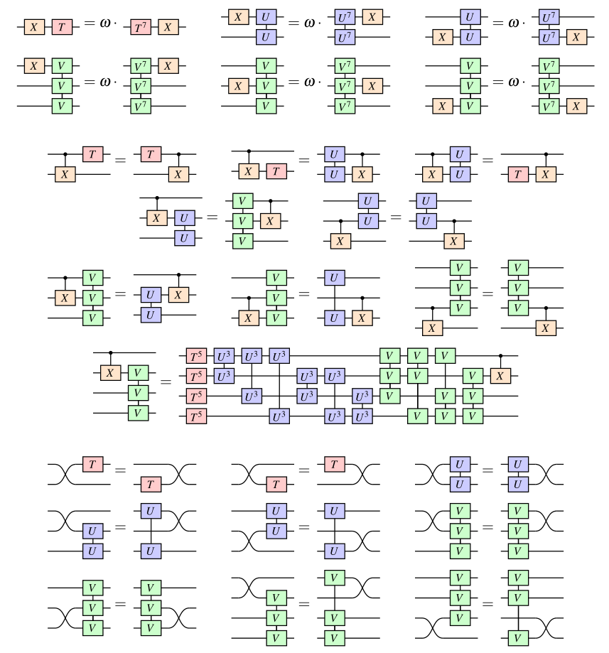

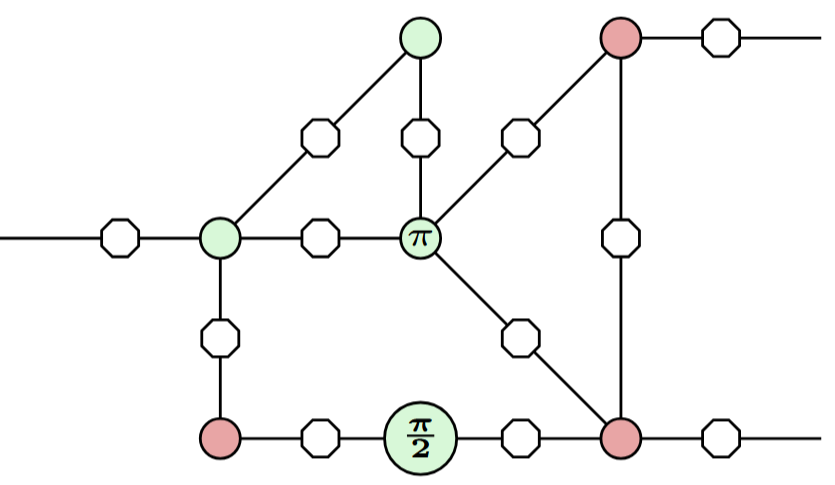

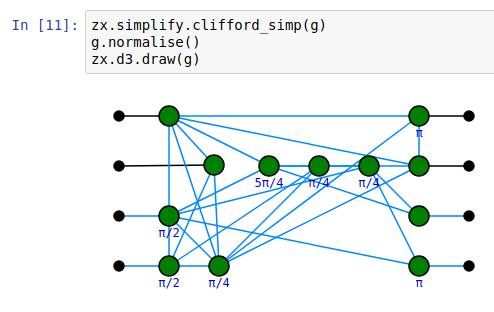

A better idea: the ZX calculus

A complete set of equations for qubit QC

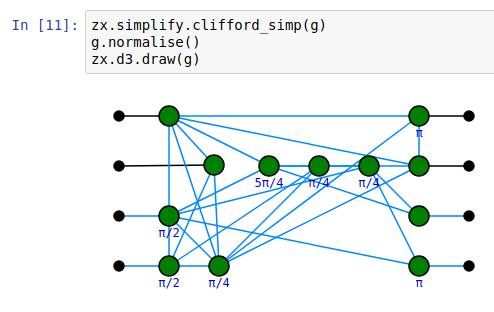

PyZX

- Open source Python library for circuit optimisation, experimentation, and education using ZX-calculus

https://github.com/zxcalc/pyzx

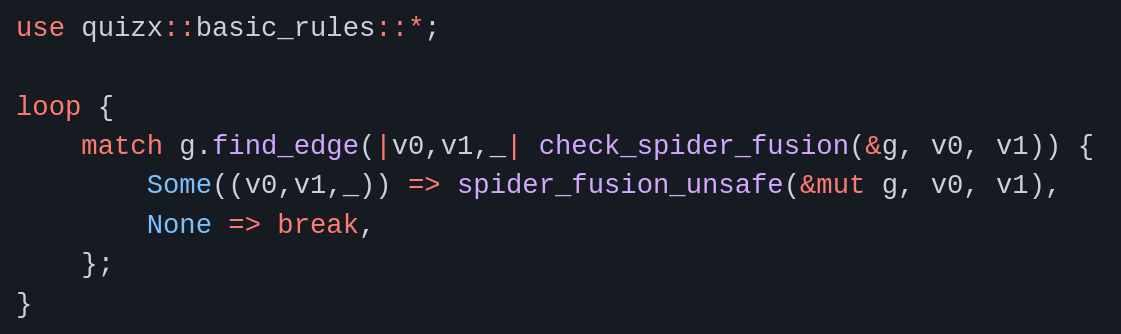

QuiZX

- Large scale circuit optimisation and classical simulation library for ZX-calculus

https://github.com/zxcalc/quizx

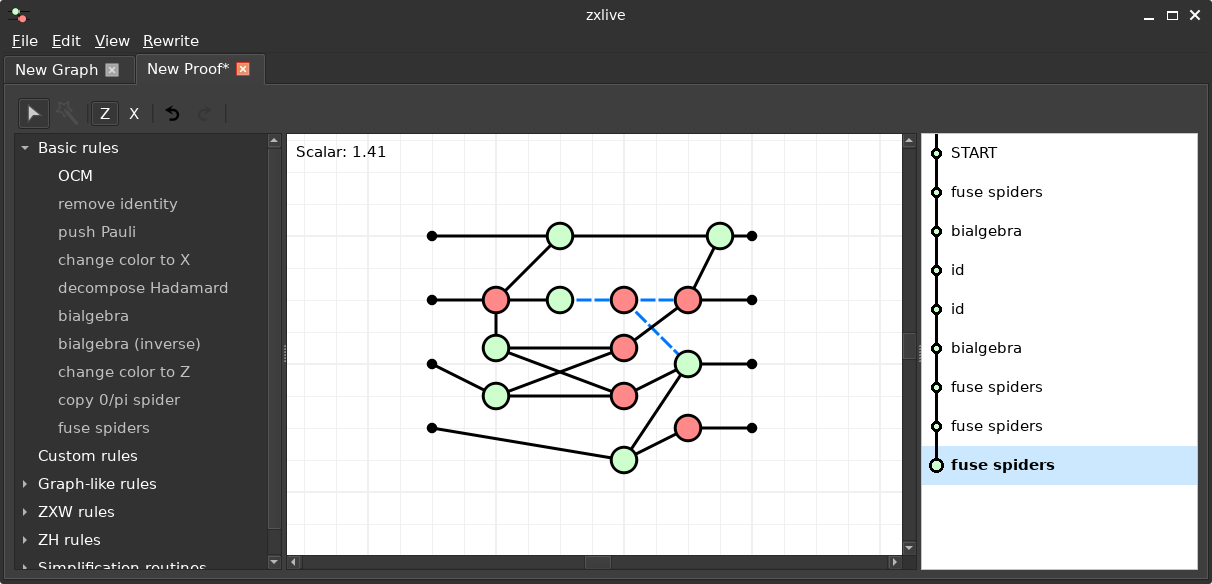

ZXLive

- GUI tool based on PyZX

https://github.com/zxcalc/zxlive

https://zxcalc.github.io/book

https://zxcalculus.com

(>300 tagged ZX papers, online seminars, Discord)

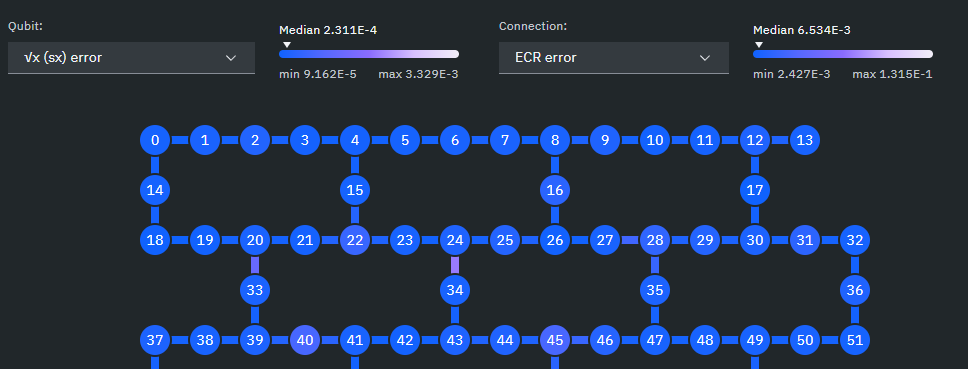

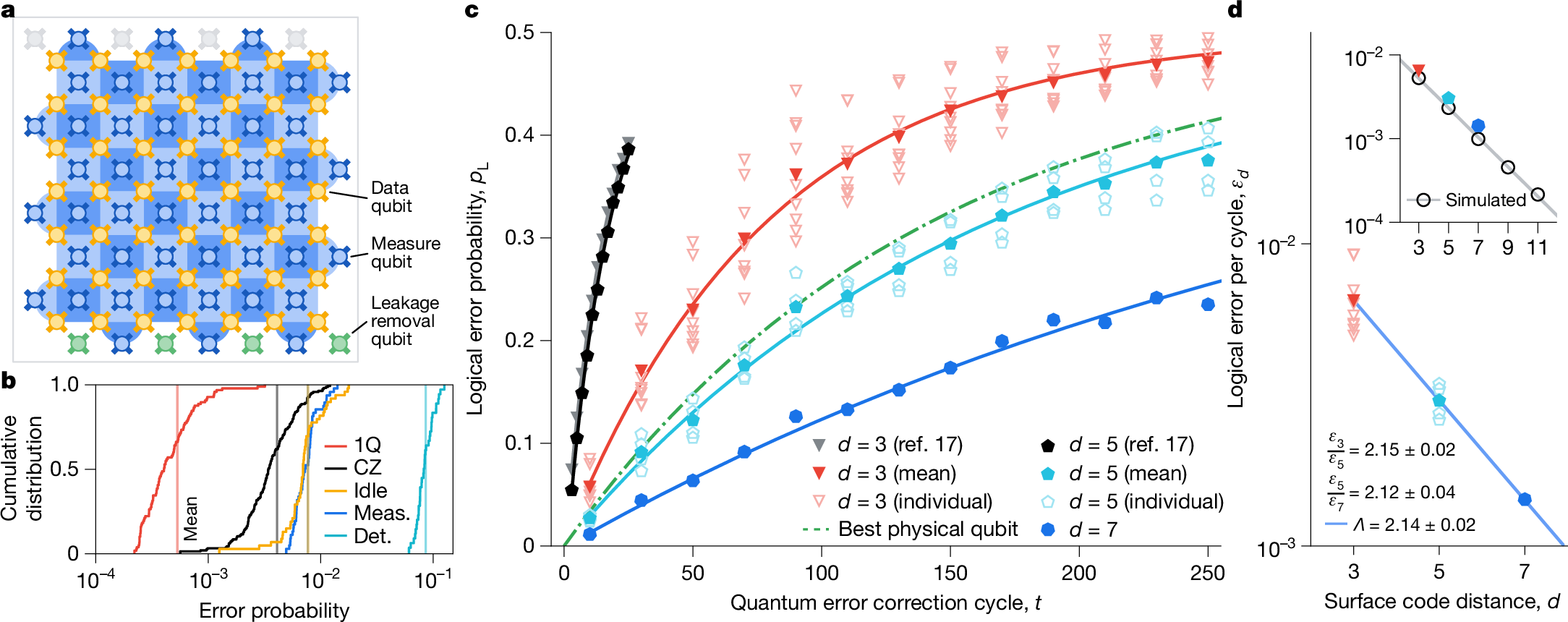

Quantum errors

- Classical error rate $\approx 10^{-18}$

- Quantum error rate $10^{-2} - 10^{-5}$

- decoherence, thermal noise, crosstalk, cosmic rays, ...

- Probability of a successful (interesting) computation $\approx 0$

Quantum error correction

into a bigger space of physical qubits:

- $E$ (or just $\textrm{Im}(E)$) is a called a quantum error correcting code

- Fault-tolerant quantum computing (FTQC) requires methods for:

- encoding/decoding logical states and measurements

- measuring physical qubits to detect/correct errors

- doing fault-tolerant computations on encoded qubits

Let's see how this works...using ZX

Ingredients

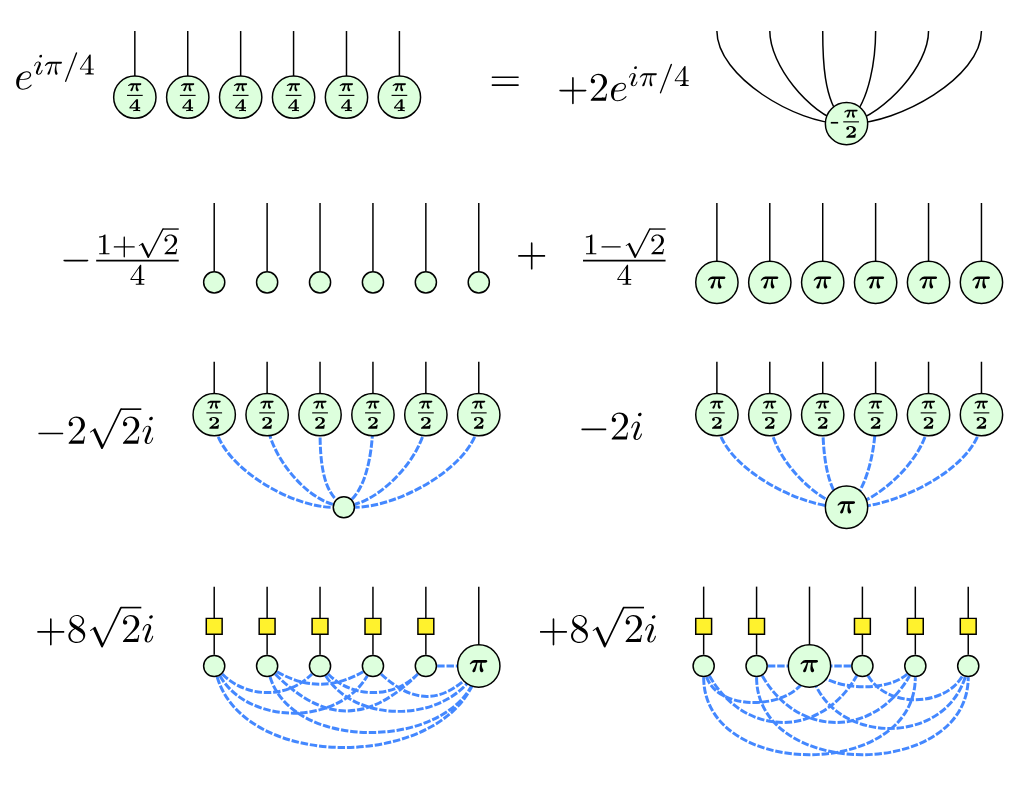

ZX-diagrams are made of spiders:

Spiders can be used to construct basic pieces of a computation, namely...

Quantum Gates

...which evolve a quantum state, i.e. "do" the computation:

Quantum Measurements

...which collapse the quantum state to a fixed one,

depending on the outcome $k \in \{0,1\}$:

Modelling errors

A simple classical error model assumes at each time step, a bit might get flipped with some fixed (small) probability $p$.

Generalises to qubits, accounting for the fact that

"flips" can be on different axes:

Modelling errors

Spiders of the same colour fuse together and their phases add:

$\implies$ errors will flip the outcomes of measurements of the same colour:

Detecting errors

We can try to detect errors with measurements,

but single-qubit measurements have a problem...

...they collapse the state!

Multi-qubit measurements

$n$-qubit basis vectors are labelled by bitstrings

$k=0$ projects onto "even" parity and $k=1$ onto "odd" parity

...the same, but w.r.t. a different basis

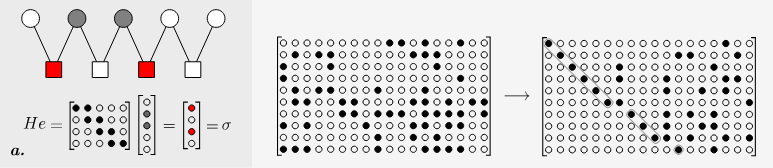

Example: GHZ code

Example: GHZ code

Example: GHZ code

giving an error syndrome.

Example: GHZ code

on a physical qubit, but it can't handle Z-flips.

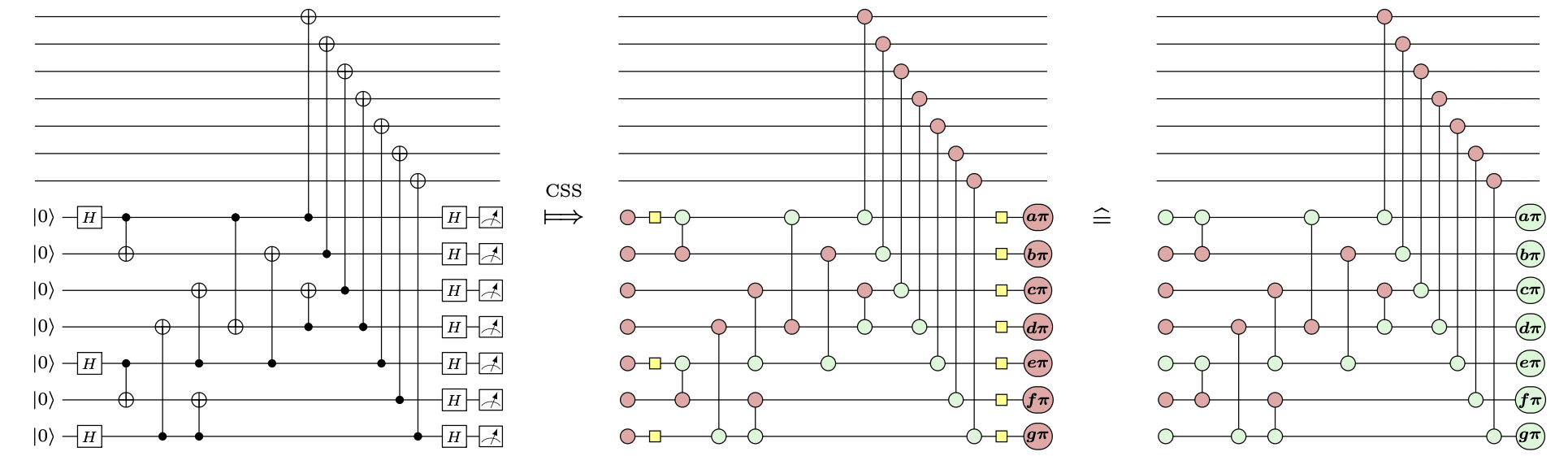

Steane code

The Steane code requires 7 physical qubits, but it allows

correction of any single-qubit X, Y, or Z error

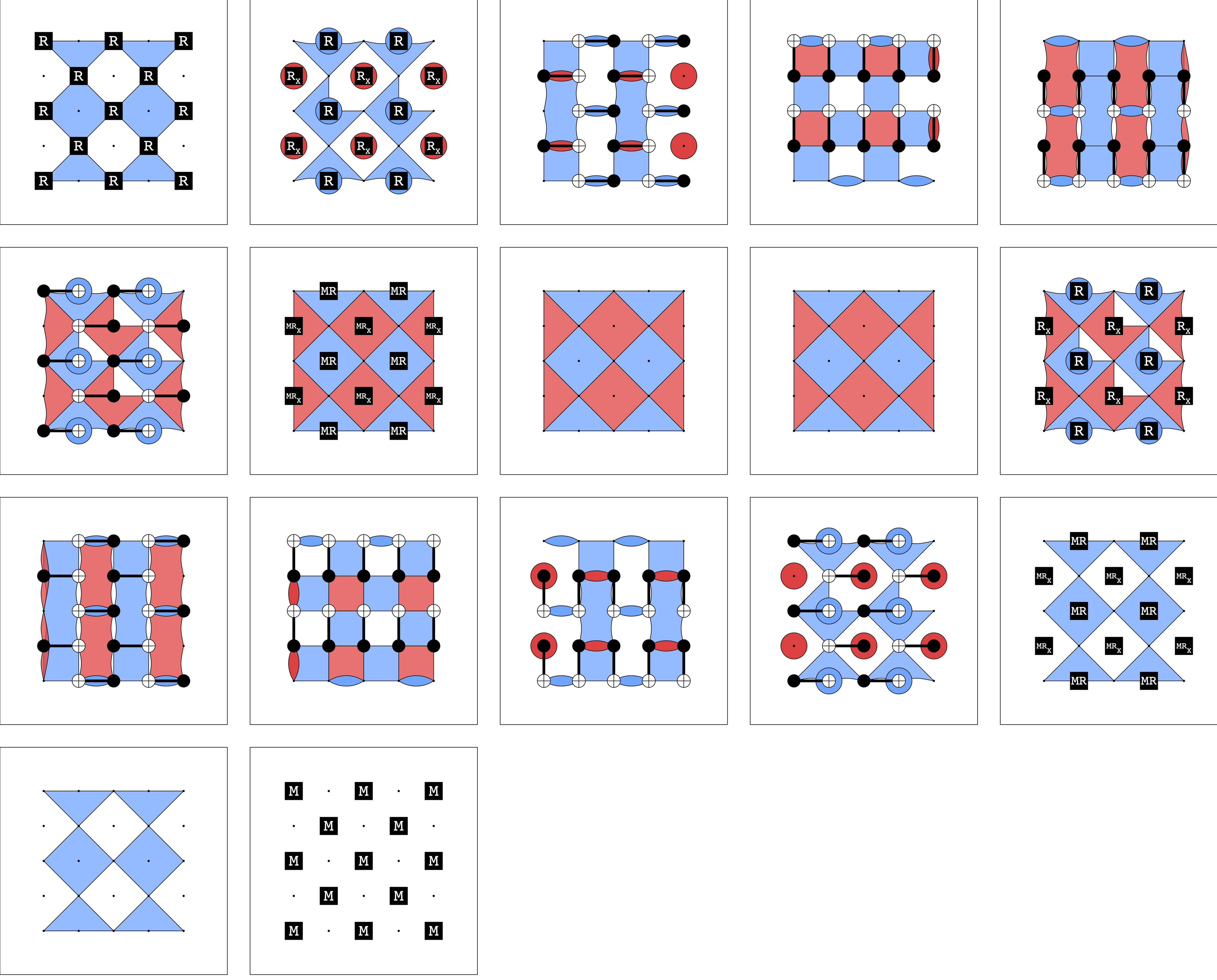

Example: Surface code

The surface code using $n^2$ physical qubits to correct $\lfloor \frac{n-1}{2} \rfloor$ errors

Problem:

Constructing good codes (esp. Good Codes)

- QEC codes are described by 3 parameters $[[n,k,d]]$

- $n$ - the number of physical qubits (smaller is better!)

- $k$ - the number of logical qubits (bigger is better!)

- $d$ - distance, the size of the smallest undetectable error (bigger is better!)

- e.g. the Surface Code is well understood and has many advantages, but its parameters aren't great ($k=1$, $d = \sqrt{n}$)

- OTOH Good LDPC Codes have amazing parameters ($k = \Theta(n)$, $d = \Theta(n)$), but are less well-understood

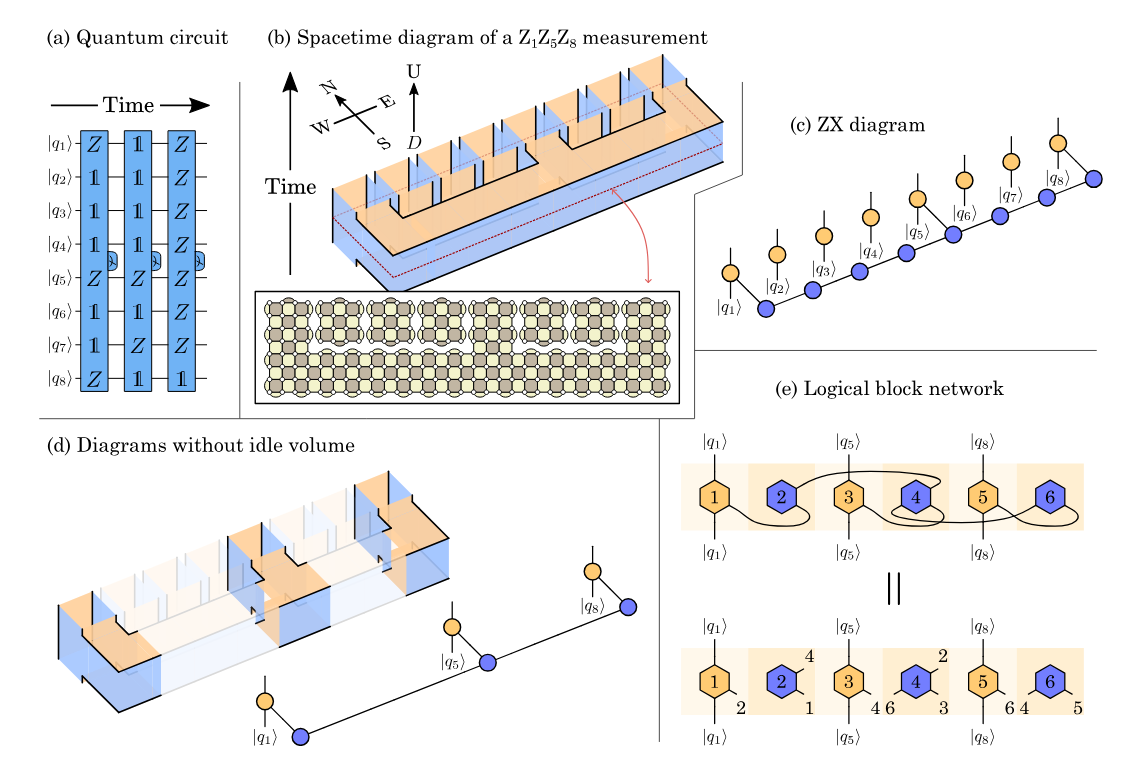

Fault-tolerant computation

But codes are only half the story. We also need to know how to implement operations fault-tolerantly.

How can we implement this?

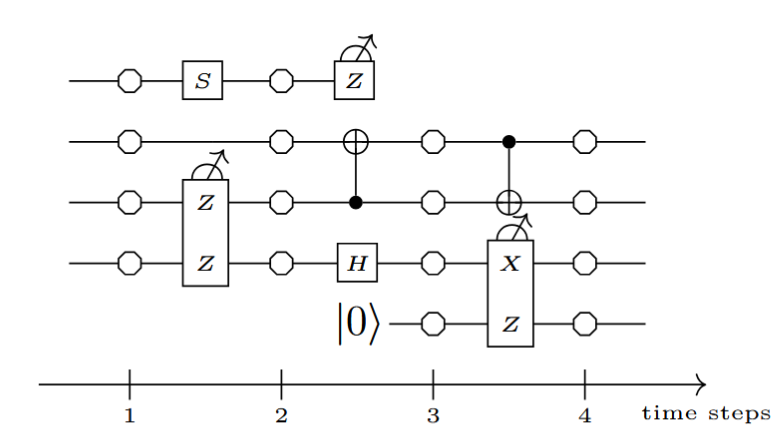

Example: measurement circuits

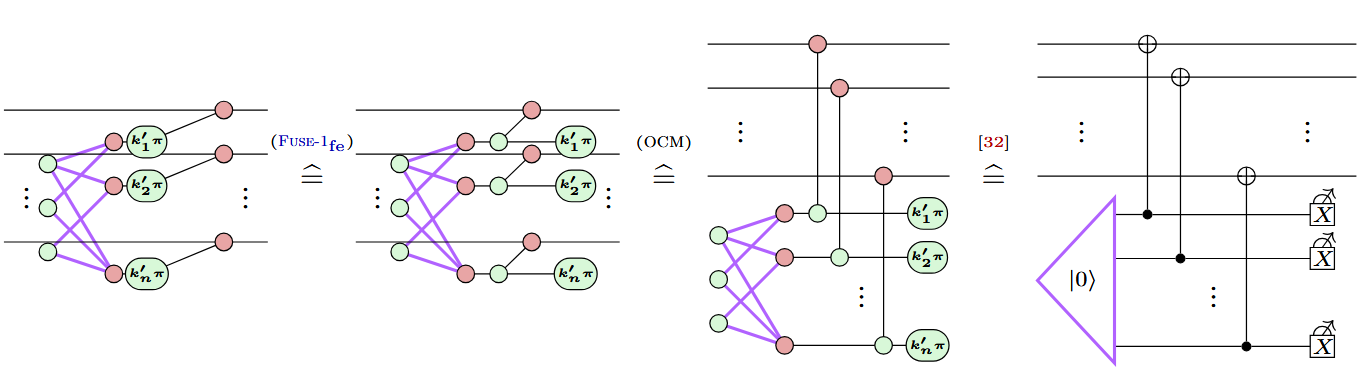

ZX can give us an answer:

Q: Is the LHS really equivalent to the RHS?

A: It depends on what "equivalent" means.

Example: measurement circuits

They both give the same linear map, i.e. the behave the same in the absence of errors.

But they behave differently in the presence of errors, e.g.

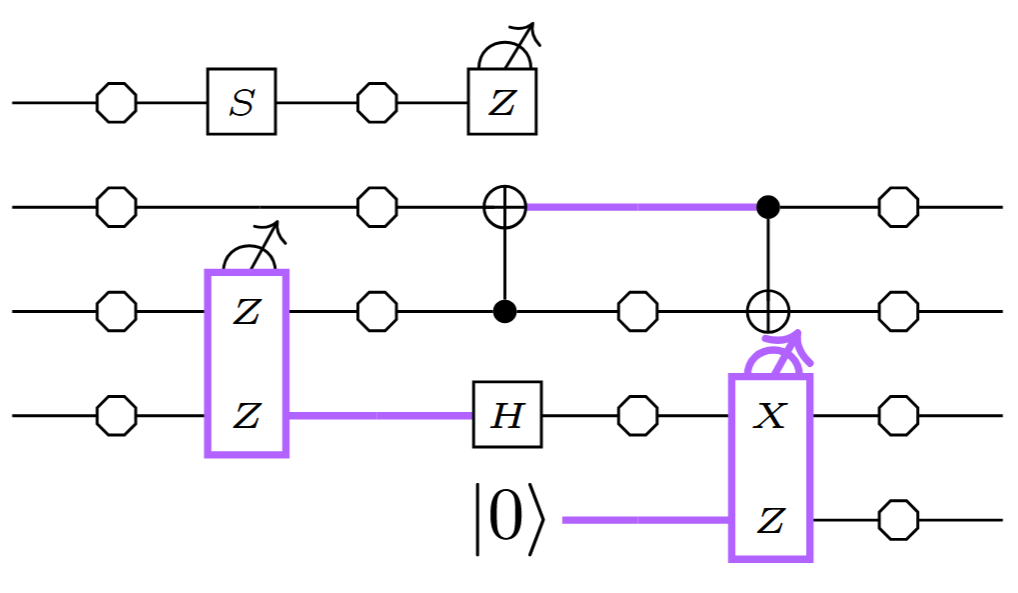

Solution: Fault equivalence

What we need is a notion of equivalence that captures the behaviour of circuits (or ZX-diagrams) in the presence of errors, fault-equivalence:

$D \ \hat{=}\ E$

$D\ \hat{=}\ E \implies D = E$

$D = E \ \ \not\!\!\!\implies D\ \hat{=}\ E$

Error locations

Similar to space-time codes, we can model faults by tracking their locations in a circuit or ZX-diagram.

we allow them at any edge in the diagram:

Pauli error models

- For a circuit/diagram with a set $\mathcal L$ of fault locations, a fault is a Pauli

$F \in \mathcal P_{|\mathcal L|} := \{ P_1 \otimes \ldots \otimes P_{|\mathcal L|} \ $ $:\ P_i \in \{I, X, Y, Z\}$ $\}$

- A Pauli error model is a choice of basic faults $F_1, \ldots, F_b$. The weight of a fault is the number of basic faults in its product.

- Ex: Phenominological/naive model:

basic faults $:=$ all single-qubit Paulis

- Ex: Circuit-level noise model:

basic faults $:=$ all single-qubit Paulis (memory errors) +

some multi-qubit Paulis (correlated gate/measurement errors)

Pauli error models

Ex: sub-models, where we remove some basic faults to represent components we assume are noise-free:

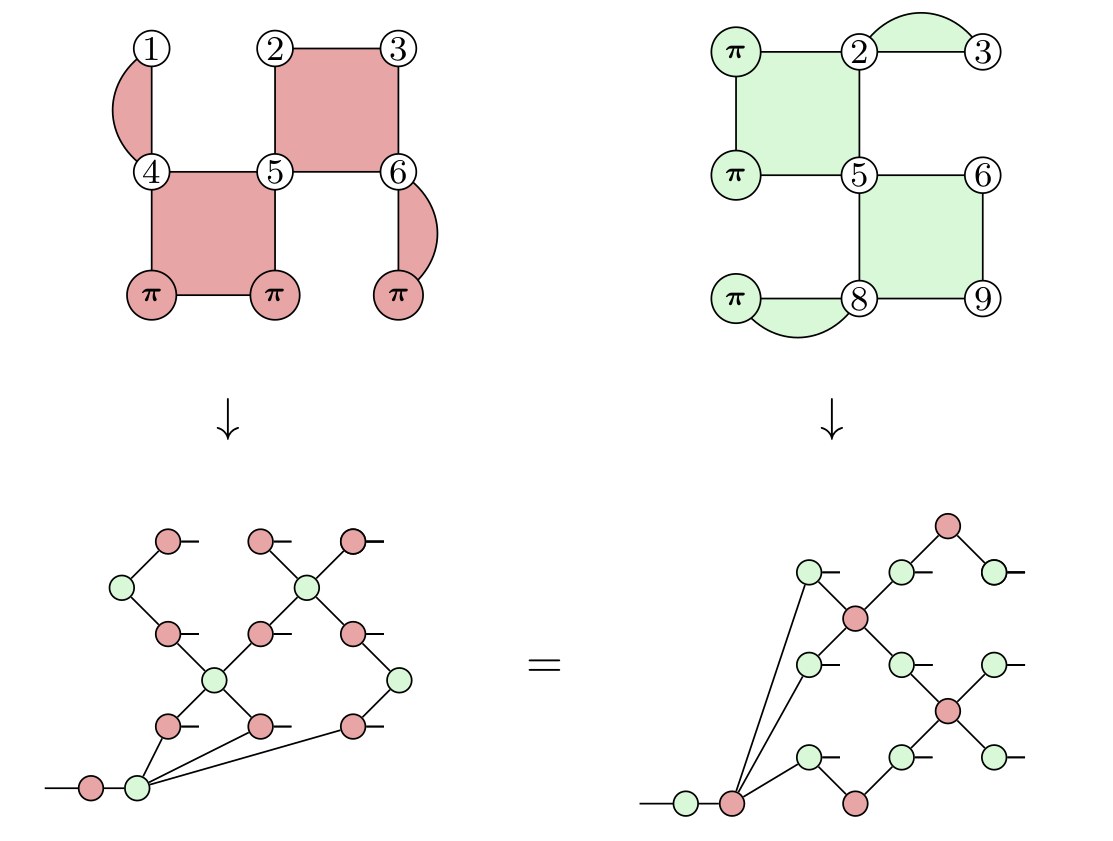

Fault-equivalence

Definition: Two circuits (or ZX-diagrams) $C, D$ are called fault-equivalent:

$C \ \hat{=}\ D$

if for any undetectable fault $F$ of weight $w$ on $C$, there exists an undetectable fault $F'$ of weight $\leq w$ on $D$ such that $C[F] = D[F']$(and vice-versa).

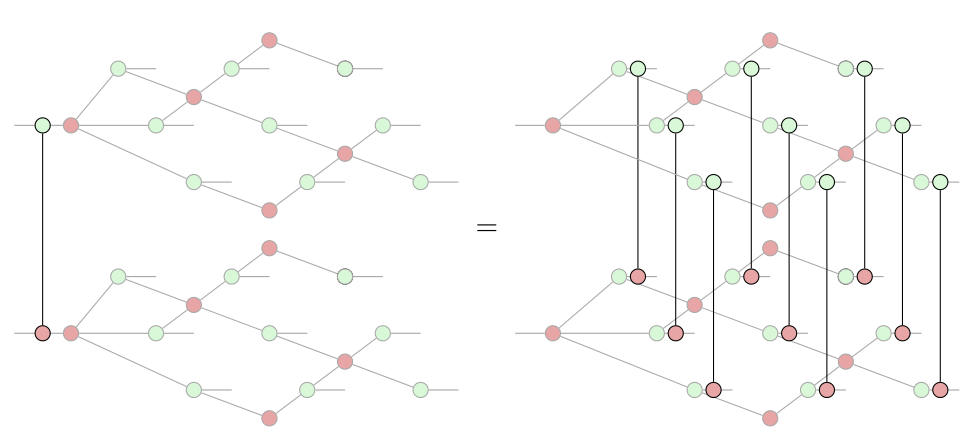

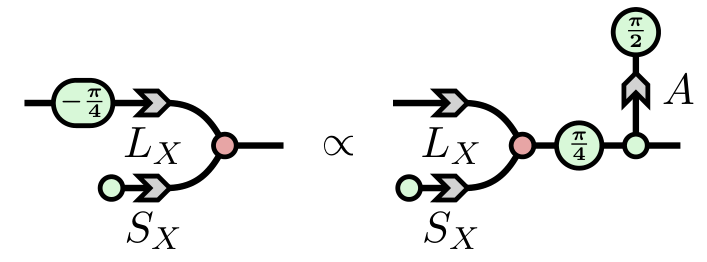

Fault-equivalence

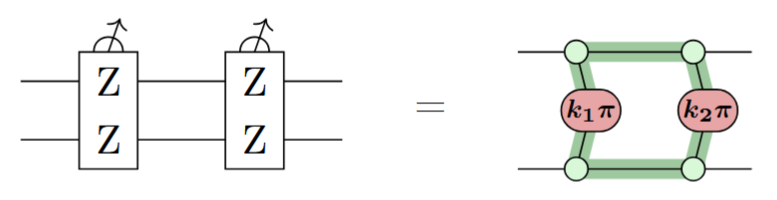

- While all the ZX rules preserve map-equivalence, only some rules preserve fault-equivalence.

- It turns out the ones that do, e.g.

...are very useful for compiling fault-tolerant circuits!

Paradigm: Fault-tolerance by construction

Idea: start with an idealised computation (i.e. specification) and refine it with fault-equivalent rewrites until it is implementable on hardware.

Specification/refinement has been used in formal methods for classical software dev since the 1970s. Why not for FTQC?

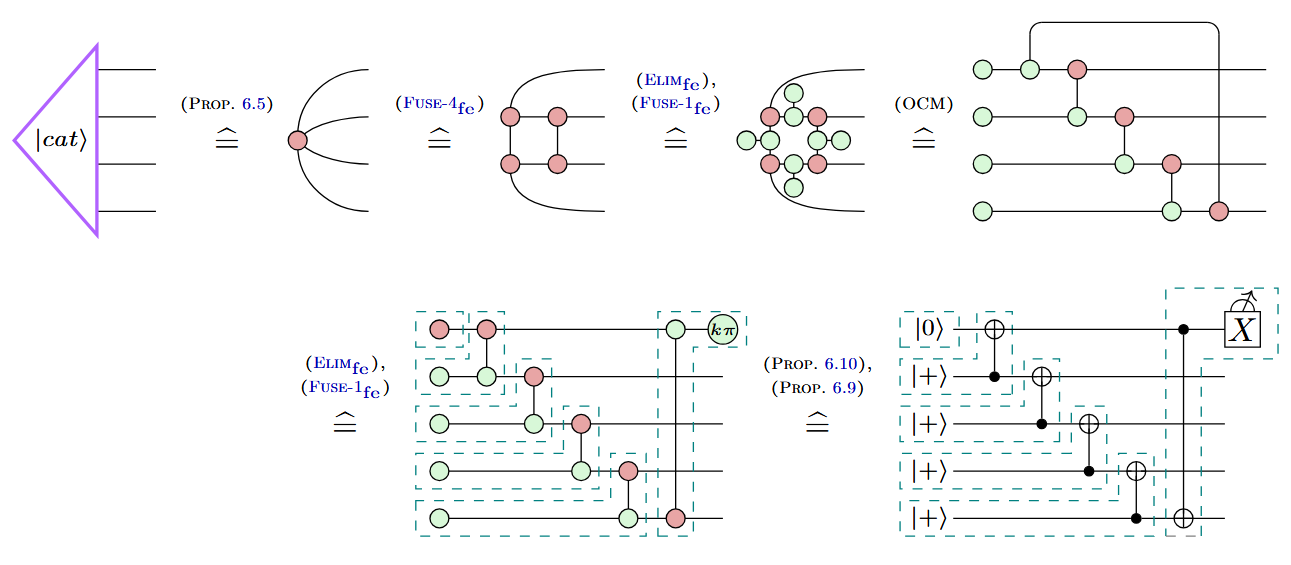

Example: Cat state preparation

Example: Cat state preparation

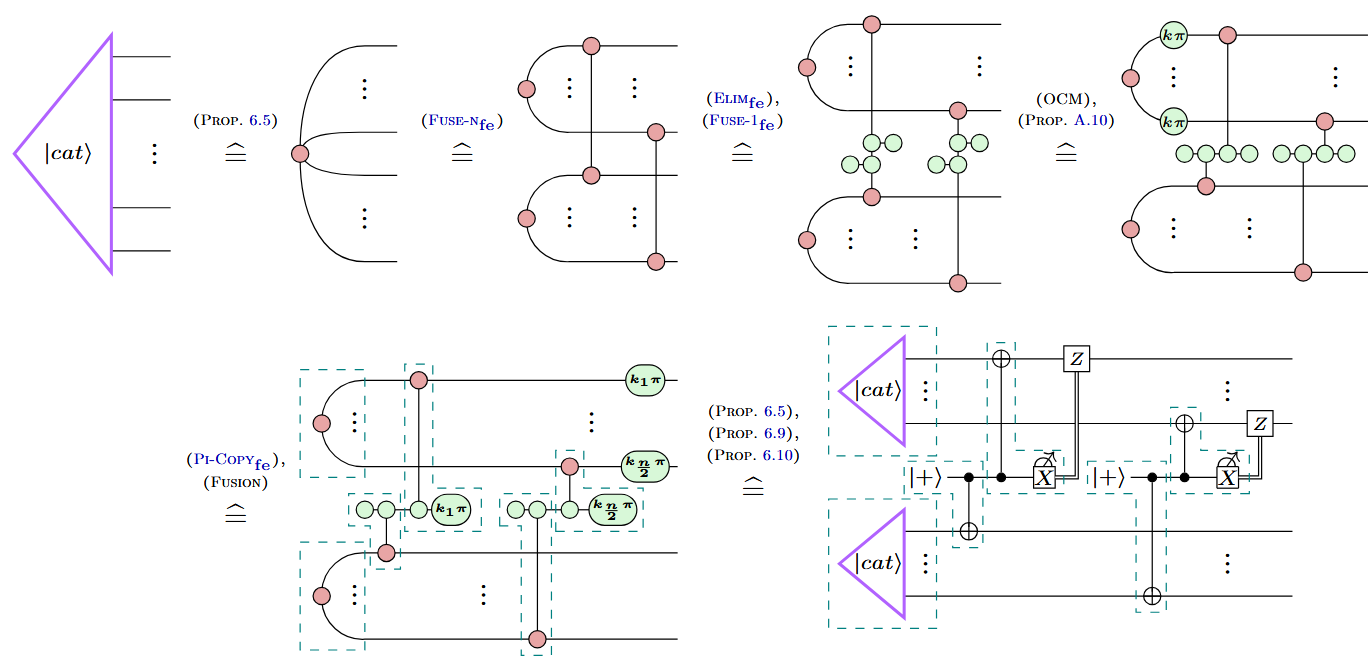

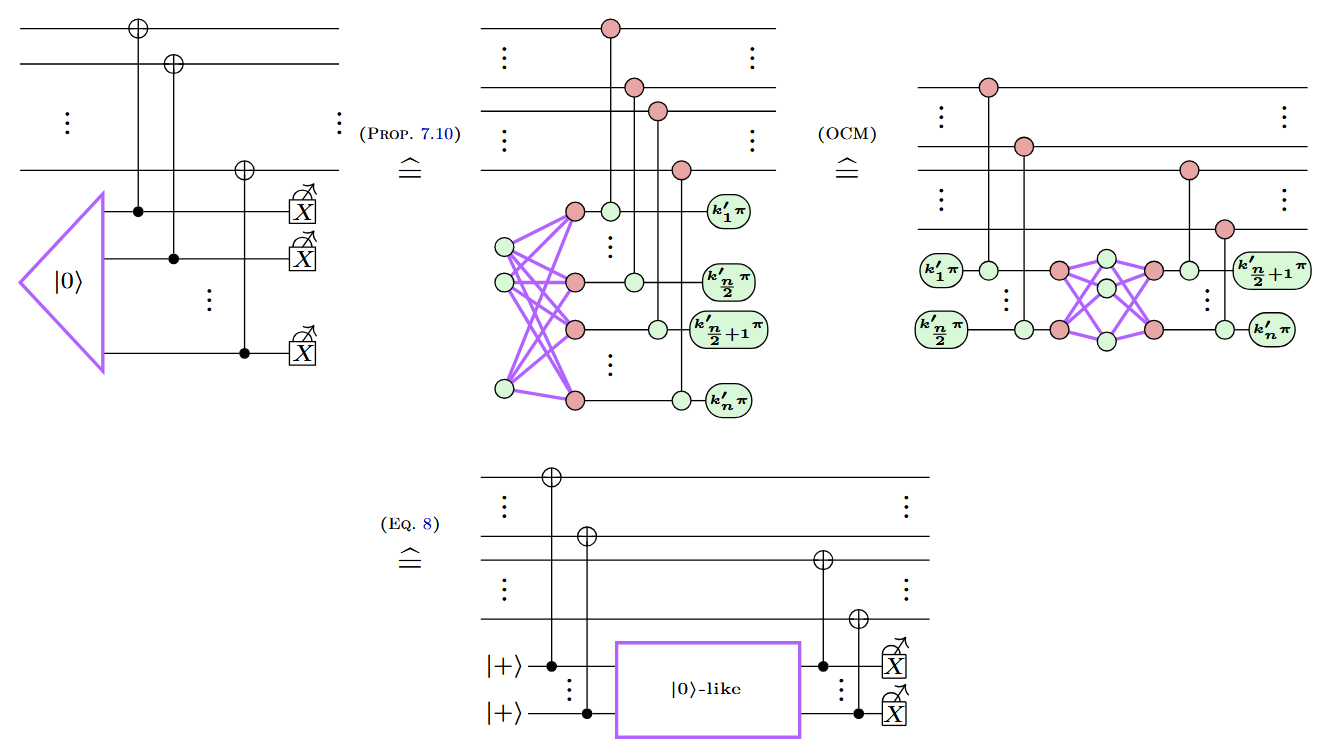

Example: Shor-style syndrome extraction

Example: A new variation on Shor

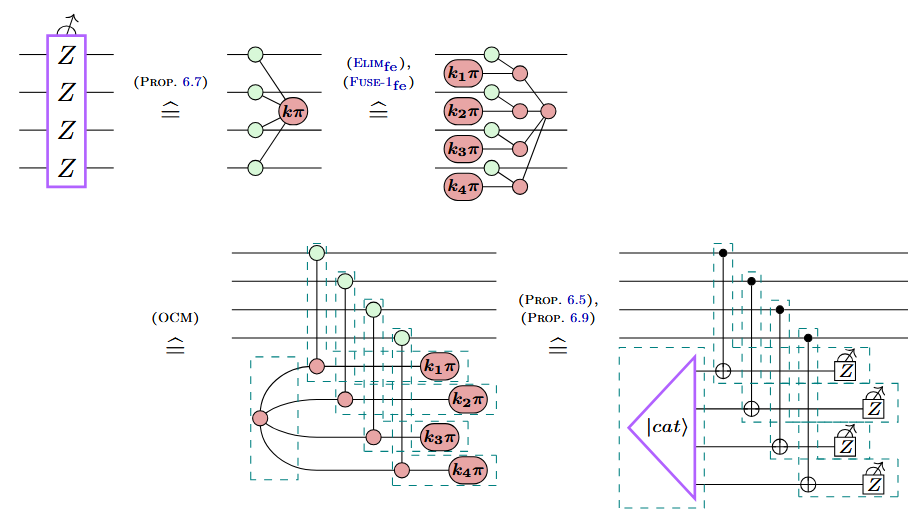

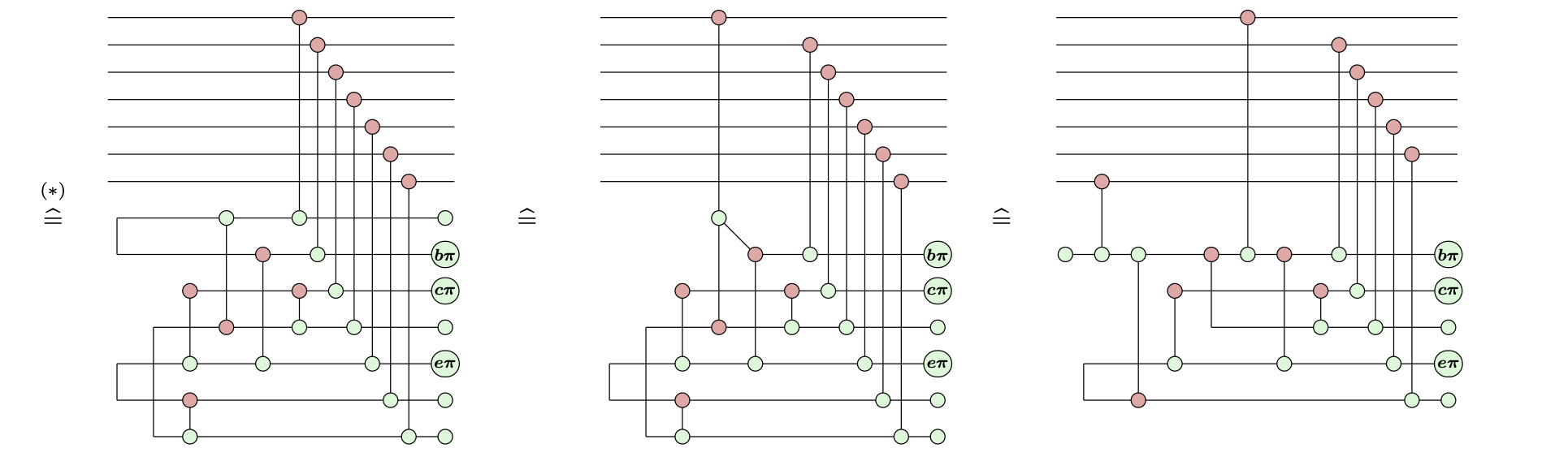

Example: Steane-style syndrome extraction

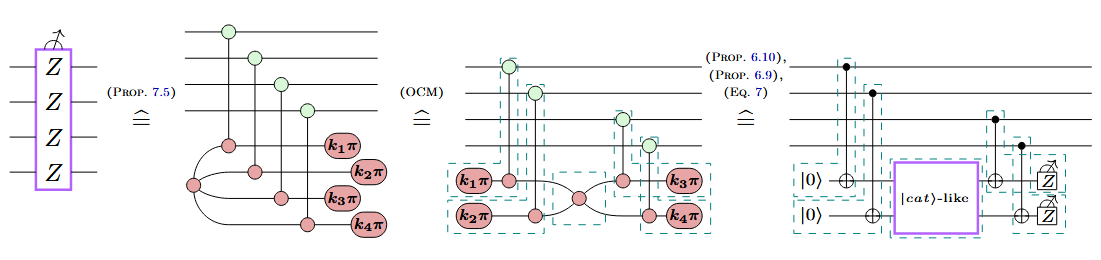

Example: A new variation on Steane (the same trick)

...with fewer qubits and a lower logical error rate!

Ultra-low Overhead Syndrome Extraction for the Steane Code

Best known circuits for this (17% lower logical error rate vs. SotA in 2025)

Lots to do!

- Automatically building/optimising FT circuits

(e.g. via heuristic search or AI)

- Logical computation and measurement

(esp. in non-traditional QEC paradigms, like dynamical codes)

Lots to do!

- Scalability / compositionality

- Tooling, automation, and integration

(PyZX/QuiZX/ZXLive/Stim)

Lots to do!

- Decoding errors and preserving efficient decodability

- Reasoning about stochastic noise

(fault-equiv. = adversarial/worst-case noise behaviour)

Image credit: Riverlane and Google Quantum AI

"Fault Tolerance by Construction". Rodatz, Poór, Kissinger

arXiv:2506.17181

- Floqetification: arXiv:2410.17240

- Completeness: arXiv:2510.08477

- Low-overhead syndrome extraction: arXiv:2511.13700

https://zxcalc.github.io/book

(free book! Ch 12 = ZX + QEC)

https://zxcalculus.com

(350+ ZX papers, 40 on ZX+QEC, online seminars, Discord)