Worksheet 2: Rotations and reflections

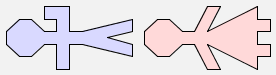

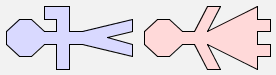

Another two functions that can be used on (or applied to)

pictures are rot and flip.

The function rot stands for rotate, and twists a

picture anticlockwise by 90 degrees. The function flip reflects a picture about a vertical axis, so it

looks like the picture has been flipped over:

rot(man) |  |

flip(man) |  |

rot(flip(man)) |  |

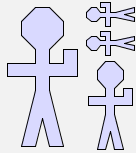

Look carefully at the first and third pictures above -- they are not the same!

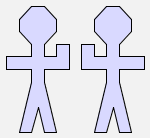

Since rot and flip are functions, they

can be applied several times to an argument. For example, rot(rot(man)) produces the following image:

rot(rot(man)) |  |

Similarly, flip(flip(man)) is allowed, although this will simply produce the original picture of man. Try it out for yourself in GeomLab.

What will rot(rot(rot(tree))) look like? Sketch the image in the space below:

rot(rot(rot(tree))) |  |

Check your answer in GeomLab.

Since the function rot rotates a picture, it should be possible to get back to the original picture by using rot several times. Fill in the expression missing in the

space below -- you must use the function rot

at least once, so don't just write "tree"!

|  |

Check your answer in GeomLab.

So far we've used rot and flip on just constant pictures

like man and tree.

Now let's try the expression rot(man & woman):

rot(man & woman) |  |

Using the picture as a guide, how can this expression be rewritten using only the functions rot and $? Fill in the expression below:

|  |

Check your answer in GeomLab.

Generally it's true that

rot(p & q) = rot(p) $ rot(q).

Is it also true that

rot(p $ q) = rot(p) & rot(q)?

Try it out on some examples in GeomLab, and see if the images produced are the same.

If the two expressions are not the same, suggest an equation that is true.

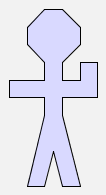

We can create a variety of different images using the functions rot

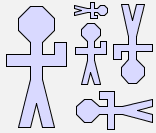

and flip on the constant picture man:

man |  |

rot(man) |  |

rot(flip(man)) |  |

How many different pictures are there? How many pictures can we

create using the functions rot and flip?

Now try to find expressions that result in these pictures:

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

For this last picture, you will need the constant picture star, and it may help you to make the star be the right size if you know that blank is a square picture

that is entirely blank.

In this sheet, we have added more operations to our algebraic

language of pictures, so that we can now rotate and reflect pictures

as well as putting them side-by-side or one above another.

In addition to adding more operations, we have also found new

algebraic identities that relate the operations to each other.

Some of these identities make it possible to move instances of rot and flip inwards in any expression, so

that it becomes a combination (using $ and &

of rotated or reflected primitive tiles. This is more-or-less what

the computer does in order to draw the pictures your program

creates.

In a wider computer science setting, similar algebraic identities are used internally by compilers, the programs that translate high-level programs written by human programmers into the low-level instructions that a machine can follow step by step. The compiler can use algebra to simplify the low-level program it creates, for example by deleting two operations if they cancel each other out. This makes the low-level program smaller to store and faster to obey.