Worksheet 4: Recurrences and recursion

Suppose we want to draw rows of men of different lengths. It would

be useful to have a function manrow(n) that, for any

value of n, would give a row of n men. How

can we define this function so that it works for any value of n .

For example manrow(4) would be a row of 4 men; let's

call that picture r4:

define r4 = man $ man $ man $ man |  |

Similarly, let us call a row of five men r5:

define r5 = |  |

What relates r4 and r5? How can we go

from a row of four men to a row of five men? We just need to add

another man! So we can say:

r5 = r4 $ man.

Similarly, we can say that r4 = r3 $ man

if r3 is a row of three men.

Writing your answers in the same way, work out equations for r3 and r2.

The expression r1 refers to a row of just one man, which is

the same as the expression man. Hence we should write the

equation

r1 = man.

It would be ideal if we could define a function manrow

that can take a number as an argument, and produce a row of men that

is as long as that number. The way to do this is tricky to understand,

so look at the definition below, and then read the explanation that

follows it:

define manrow(n) = manrow(n-1) $ man when n > 1 | manrow(1) = man;

This definition of the function manrow consists of two

equations, separated by a vertical bar character |.

The first equation is used when n > 1, and states in

general form our observations that r4 = r3 $ man, and r3 = r2 $ man, and so on.

The other equation is simpler, and just restates the fact that r1 = man in terms of the function manrow.

You should enter this definition into GeomLab. On a British PC keyboard,

the symbol | is entered by holding down the Shift key

and pressing the \ key, just to the left of the Z.

At first sight, this equation appears to be defining the function manrow in terms of itself, and because of this, we call

it a recursive definition.

Despite the self-reference, the definition works

because it shows us how to calculate, say, manrow(5)

assuming we already know how to calculate manrow(4), and

applying the equation repeatedly can bring us down to the base case manrow(1) = man.

Having defined manrow as aboive, if you type an expression like

manrow(5), then GeomLab expands the definition like this:

manrow(5) = manrow(4) $ man = manrow(3) $ man $ man = manrow(2) $ man $ man $ man = manrow(1) $ man $ man $ man $ man = man $ man $ man $ man $ man.

The result is the image we expected:

manrow(5) |  |

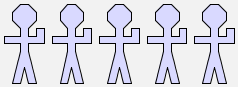

What does manrow(4) & manrow(3) & manrow(2) look like?

Sketch the picture here:

manrow(4) & manrow(3) & manrow(2) |  |

This picture looks a bit like a crowd, so let's try to define a function that can create crowds of different sizes.

To get a realistic-looking crowd, we will need to have rows that

get larger in the number of men (and smaller in height) as we travel

from bottom to top of the picture. The function crowd(m, n) can be

defined so that m is the length of the bottom row in the

picture, and n is the length of the top row. To save

ourselves work, we can use the previously defined function manrow to draw the rows that we want.

If m and n are the same, then the crowd

will consist of just one row:

crowd(m, m) = manrow(m)

Otherwise, we are considering an expression of the form

crowd(m, n), where m < n.

This crowd consists of a top row containing n men, and

below it a smaller crowd with rows ranging from m

to n-1 men:

crowd(m, n) = manrow(n) & crowd(m, n-1)

We can put these two equations together to make a recursive

definition of the function crowd:

define crowd(m, n) = manrow(n) & crowd(m, n-1) when m < n | crowd(m, m) = manrow(m)

Here are two example images produced using our crowd

function:

crowd(3, 5) |  |

crowd(6, 12) |  |

Try it, by putting the definitions of both manrow and crowd together one with one of these expressions, all in the same text.

This sheet has introduced an important new idea: that we can take a recurrence relation that describes a sequence of pictures, and turn it into the definition of a recursive function that generates pictures in the sequence. Simple recursive definitions have two parts: a rule that generates an element of the sequence from the previous element, and a starting rule that defines the first element. The idea of defining functions recursively is important, because it opens the possibility that a finite program can generate an infinite variety of behaviour by varying the argument that is passed to the function.

With a non-recursive function, each time the function is referred to, the formula that is the body of the function is used just once. With a recursive function, substituting the body of the function for a use of it may leave a formula that still contains a use of the function, so the definition may be used many times in computing the value of the function. In a wider setting, it is recursion that lets us use functions to model, understand, and compute with complex processes.