Worksheet 7: Space-filling curves

Hilbert curve

By now, I hope you will relish the challenge of working out how to draw pictures without much help from me. If so, here are two families of pictures that are made up from square tiles.

The first family was discovered by the German mathematician David

Hilbert (1862–1943), and can be made with the bend and straight tiles that we used earlier:

bend |  |

straight |  |

The first curve in the family (let's call it hilbert(1)) consists of four copies of bend, rotated and joined together:

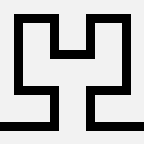

hilbert(1) |  |

The next curve is a little more complicated:

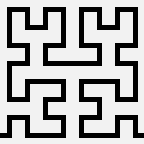

hilbert(2) |  |

With the third curve in the sequence, a pattern starts to emerge:

hilbert(3) |  |

It looks as if this curve is made up of four copies of hilbert(2) rotated and joined in the right way.

But if you look closely, you will see that in each copy of the curve,

one of the ends has been bent so as to make it join with the next part

of the curve, so that hilbert(3) actually consists of

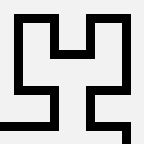

four copies of different picture – let's call it hilbend(2):

hilbend(2) |  |

To draw the Hilbert curves properly, you will need to define two recursive functions that depend on each other. You can

begin to work out their definitions by asking what hilbend(1) would need to look like if it had the same

relationship with hilbert(2) that hilbend(2)

has with hilbert(3).

What should hilbend(3) look like, and can it be made

from copies of hilbert(2) and hilbend(2) put

together in an appropriate way?

Does the sequence have to start with hilbert(1)? Is there an

appropriate definition of hilbert(0) that fits the pattern?

These hints should be enough for you to define the two functions

for yourself. When you have done so, what happens if you evaluate hilbert(10)? Does this justify the term space-filling curve that is used to describe the behaviour of curves in this family?

Sierpinski curve

Another family of space-filling curves was discovered by the Polish

mathematician Waclaw Sierpinski (1882–1969). This can be drawn using

two new tiles that we shall call nub and link:

nub |  |

link |  |

We can make the first curve in the family using four copies of nub:

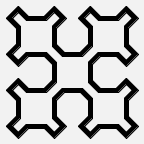

sierp(1) |  |

The next member of the family is almost but not quite four copies of this picture joined together:

sierp(2) |  |

The third member is similarly obtained from four pictures that are

not quite the same as sierp(2):

sierp(3) |  |

Can you write a recursive definition of the function sierp,

perhaps by defining it together with another function, so that they

are mutually dependant?

These two families of curves are called space-filling because (in a precise sense) the curves come close to every point in the square that encloses them. By using some results about continuous functions that are proved in university-level maths, it is possible to use these curves to show a seeming paradox, that there is a continuous function that maps the unit interval to the whole of the unit square.

From a programming point of view, the interesting thing is that – like the Escher picture – these curves are made up of several pieces, each similar to the curve itself.